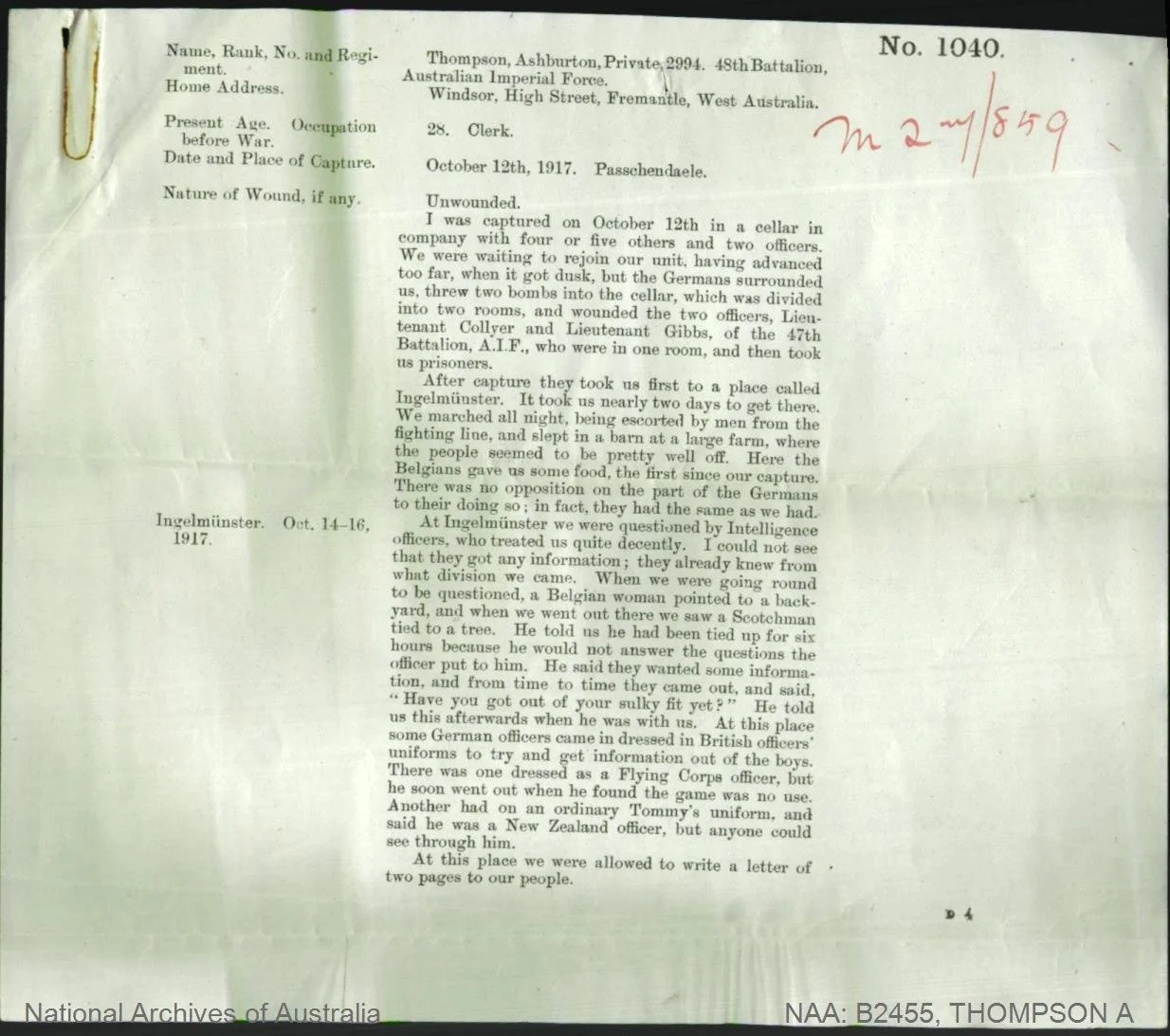

I was captured on October 12th in a cellar in company with four or five others and two officers.

We were waiting to rejoin our unit, having advanced too far, when it got dusk, but the Germans surrounded us, threw two bombs into the cellar, which was divided into two rooms, and wounded the two officers, Lieutenant Collyer and Lieutenant Gibbs, of the 47th Battalion, A.I.F., who were in one room, and then took us prisoners.

After capture they took us first to a place called Ingelmünster. It took us nearly two days to get there. We marched all night, being escorted by men from the fighting line, and slept in a barn at a large farm, where the people seemed to be pretty well off. Here the Belgians gave us some food, the first since our capture. There was no opposition on the part of the Germans to their doing so; in fact, they had the same as we had.

Ingelmünster. Oct, 14 - 16, 1917

At Ingelmünster we were questioned by Intelligence officers, who treated us quite decently. I could not see that they got any information; they already knew from what division we came. When we were going round to be questioned, a Belgian woman pointed to a backyard, and when we went out there we saw a Scotchman tied to a tree. He told us he had been tied for six hours because he would not answer the questions the officer put to him. He said they wanted some information, and from time to time they came out, and said, “Have you got out of your sulky fit yet?” He told us this afterwards when he was with us. At this place some German officers came in dressed in British officers’ uniforms to try to get information out of the boys. There was one dressed as a Flying Corps officer, but he soon went out when he found the game was no use. Another had on an ordinary Tommy’s uniform, and said he was a New Zealander officer, but anyone could see through him.

At his place we were allowed to write a letter of two pages to our people.

We were put in barracks, and were fed better here than anywhere else; in fact, it was the only place we really did get food ; it was rough but sufficient. We got a sufficient ration of bread, soup in the middle of the day, turnip and beetroot jam at night. It is a big clearing station, and it was all that we could expect.

We were kept at Ingelmünster three days, and then taken by train to Termonde. The journey took the inside of a day. We were treated decently on the way and in the train. Our guard were Saxons.

Termonde Barracks. Oct 16-19, 1917

When we arrived at Termonde they put us into the old Belgian military barracks. The room we were in was nice and warm, and we slept on straw. We were only in this place for three days; the straw was clean, and there were decent sanitary arrangements. The food was very bad. We had 2-lb loaf of black bread for seven men per day, a bowl of vegetable soup for dinner, and the same for supper. There was no substance in the soup, and we were on the verge of starvation.

There were a number of Belgian workmen doing the place up, and the boss could talk English. He used to speak a lot to us, and told us they were expecting a lot of conscientious objectors, German soldiers from the fighting line, about 3,000 of them, and he said he would not be surprised if there were a lot more. I suppose he knew some of the guards and they used to talk to him. He seemed to think the German soldiers were fed up with the war. He also told us a new German order had come out saying that they must deliver up all the wool that was in their beds and pillows on a certain date, and stuff them with paper instead. There is no doubt that there is great distress in Belgium. There were some girls working in the barracks here, and I heard them ask the sergeant if he had any spare bread. Coming along, I had noticed men and women pulling barrows over the ground; I am certain they had no horses. At the farm we were stopped at on the way up they seemed altogether better off. A lot of our boys had money with them, and they changed it for German money at this farm, and got tobacco, of which the men here seemed to have plenty. The contractor at the barracks said they were very short of food. There is no such thing as soap and butter in Belgium.

Woolen factory. Oct 12 - 24 1917

After three days we were shifted across to the other side of the canal, and put in an old woollen factory. It had a glass roof, very high walls and cement floors. It was very very cold in here; they were putting in a stove the day before I escaped. Here we met about 272 other British soldiers, mostly the Buffs (there was a company of them), Irish Guards, Durhams, Highland Light Infantry and some Australians. Some of the men here had been at Termonde for three or four months, and they were longing to get sent into Germany. A draft of men who had been there some months had been sent to Germany just before we arrived, and we were told our lot would not be sent for about the same period. We were told they got no parcels here, but occasional letters. However, one evening I did hear something about some parcels having come in, and the German sergeant called out some names, but they were of all men who had been removed to Germany, and I believe they sent them on.

There were some wounded here, only slight cases, and the doctor came every morning. He was an old German, and quite a decent sort of man, but very rough. Two or three were sent into the town to hospital during the 12 days I was there, and we heard they treated our soldiers well there.

The commandant was a captain. He came and asked if there were any complaints just as a matter of form.

They gave you no clothing until you had been here three or four months. There were no baths, and the place was very verminous.

There were a number of Russians working outside, and we heard (through a Russian that was with us) some had been there two years. I saw no Belgians working.

You were allowed to smoke, if you could get any tobacco, but it was very difficult to get.

There was only a small yard to exercise in during the day. There was no work to do, and no books or anything.

At this place we slept on straw; they brought in five or six wagon loads, very dirty and damp, from another big woollen factory near where the Russions had been living and sleeping. It was very verminous. The sanitary arrangements were all right, except that we had no soap or towels. We had no blankets. Some officers had tried to get some for the men, but some of those who had been here for months had none; a few had one and a cotton oil sheet. It was frightfully cold and you got very little sleep. I had no greatcoat.

The food here was awful. You got a 2-lb. loaf of black bread for seven men in the morning, with acorn coffee and no milk or sugar. One morning you would get a 2-lb. tin of meat for 15 men; the next morning it would be just the dry bread; the following morning you got a little something that looked like butter, but had no greasy taste and was neither butter nor margarine. Next morning we had a tin of black pudding, as they called it, made of horse blood, a tin of 1 lb. for seven men, but you had to be pretty hardy to eat this. For dinner and supper we had a bowl of vegetable soup, sometimes mixed with salty fish roe. These two meals were the same every day. You could buy apples and a little tobacco from a German corporal who ran a bit of a canteen and made a small profit. You were practically starved here. If you bought an apple and threw the core or a bit of peel down, it hardly reached the floor before someone picked it up and ate it. Outside the yard is a gate, and I have seen the men put their hands under and children outside would give them bits to eat. If the sentries came along they would kick them away. I was disgusted at first, but you can understand it. When there were only a few prisoners here some Belgian women came in and brought a few luxuries. Sometimes the Belgian woman would bring little parcels, a slice of bread and an apple, and try and push them under the gate, but if the sentries saw it they would push them away. They seemed to want to do what they could for the British. At one of the stations between Ingelmünster and Termonde a woman tried to give one of our boys a loaf of bread, and I heard the stationmaster say she should not do it, as the British were no friends of the Belgians, but she gave it all the same. At this same station I saw a Belgian civilian handcuffed to a Prussian guardsman.

There were a Belgian and a French prisoner with us at Termonde. The only thing I got out of the Belgian was the direction of the frontier. We had a German corporal, Australian born, named Pfenig, with us. He got on fairly well with the sentries, and was very useful to us, as he acted as an interpreter. I do not think these kind of men are really loyal. We had a Russian with us belonging to the 47th Battalion, and when we were behind the lines I saw him rush up and shake hands with the Germans. He came with us from where we were captured, and in the train one of our boys tried to throw him out the window. He is still at Termonde. There was a little English Tommy here, fat-faced (I do not know his name or regiment), who, seeing four of us together, came over to us on several occasions. He seemed a decent sort of chap, and got into our confidence. This boy had been in the camp between three or four months. He seemed to be very friendly with the sentries, and used to give him some of their food and necessaries, and if there were any outdoor jobs to be done, he used to get the preference. In the yard there were two places where it was possible for us to get out, and we told him about this, as we wanted him to get us a loaf of bread while he was outside. The same night Private Falconer saw this boy talking to one of the sentries in the yard and looking up towards these two places where we intended getting away. The following morning two Belgian workmen came and barricaded these places up, and also the same day some machinery holes were bricked up. I cannot state whether this boy was actually English or whether he was a spy.

Escape Oct 24, 1917.

On the 24th of October I escaped with two other Australians. We climbed up a steam pipe on the wall about 35 feet high, and crossed on a girder to the opposite wall, sitting on it and working our way inch by inch, and got through a skylight in the glass roof. The sentry was in the corner of the room, but fortunately did not look our way, though some of the others saw us doing it as they lay on the floor beneath; we had turned the light a little low. We then made our way to another part of the factory that was not being used, through another skylight, and dropped through onto the floor of another room, where we found an open door in the building, and made our way onto the canal about 9 o’clock at night. We had no watch, map or compass, but I have been to sea a lot and know all the stars, and we made our way by them all the time after this. It was a wet, cold night. About 10 kilometres on we struck another canal, but the bridges were all up, so we went along it till we came to a boat moored with wire at both ends, which we cut, and crossed the canal ; a watchman called out to us. This was near St. Nicholas.

Making across the fields, about 5 a.m. we reached a farm and hid in a barn; the farmer discovered us about an hour afterwards and gave us a couple of apples each. He could not speak English, but we signed to him to keep quiet; later on he brought us some hot breakfast, and afterwards some dinner. In the afternoon a girl and a woman came into the barn; the former could speak English. About 4 we had another meal, and as soon as it got dusk they took us into the kitchen, made a big fire and we dried our clothes and boots. The girl said she had a brother in the British Army. After another meal we left about 7.30.

This town is a big German centre. We heard machine guns and saw sentries; I think it is a training centre for Ostend and Bruges.

We went across country again, and next night got near the frontier and hid in a barn. The Belgian farmer found us in the morning (we meant him to), and gave us some breakfast. We asked him if we could sleep here till night; he was quite willing, but his wife objected; she was frightened of the Germans; so we left the farm and spent the rest of the day in a bed of water reeds, which was very cold. I don’t think it was pro-Germanism, but pure fright, on the part of the woman, and we didn’t expect anything better.

That night we went up to the frontier, and here struck the sentries, who were posted every 100 yards on a dyke, with guard-houses that were previously farms. This place was Kieldrecht, near Houlst. We crossed the dyke, passed the sentries in the dark and came to the electric fence, which was about 12 feet high, and is connected by cross wires from one wire to the other like a sheep fence, with wires running to within three inches from the ground. Private Falconer put his hand on the wire, and the shock knocked him back a distance of about 12 yards; he yelled out, but the sentries did not hear him, fortunately. Then he touched the barbed wire and got another shock; finally, he tried the insulators, as we thought we might be able to climb up them, but instead of the wires being twisted round, they ran straight across and made them conducting. This fence is instantaneous death if you touch it with your head or fall upon it.

The shock made Falconer very ill for some time. As we could do nothing that night, we decided to go back, get a spade, and try again the following night.

We had no food but turnips, so went back about a mile, and hid in a barn in another Belgian farm, which, like the other farms we had been in, seemed to be well stocked. The following seven nights the moon was too bright for us to make the attempt. We dared not speak to anyone, but crept out when it was dark and got beetroots and turnips to eat. Twice we walked down to the fence, and in the shade of the trees watched the sentries to see how they worked, getting the strength of their movements. A lot of German soldiers used to pass along the dyke going into the town after their work was finished, and we could hear the sentries challenging them; one night the password was “Angleterre,” and on the night of our escape it was “Australia”

On the seventh night we got a spade from the kitchen of the farmhouse, and on the eighth, the moon being favourable, we decided to make the attempt to get through. We reached the guard room and got safely over to the fence through the two barbed wire fences. Here we dug a hole about 3 feet deep between the fence at the bottom of the dyke, two of us smoothing out the soil the other threw out with our hands. We were interrupted here for about 1 and a half hours owing to the sentry standing in one position opposite us. However he was relieved, and the new sentry stopped a considerable time at the other end of the bit of dyke he was on, which gave us the opportunity to finishing our work, and we got under the fence after waiting about an hour, as the sentry came to our part of the dyke again. The moon was up by now, and it was very light. We got into a field the other side of the fence among some calves, and finally made our way to a place called Walsoorden on November 4th. When we into Dutch territory after crossing the fence we found no Dutch sentries.

We reached Walsoorden about 9 in the morning, and were in Rotterdam the same night, having been helped by a civilian, a Mr Limot, who gave us money and told us how to get to the British Consulate.

I have given all the names of the men in the 48th Battalion who were at Termonde to the A.I.F. Headquarters.

Opinion of Examiner

I consider this witness decidedly above the ordinary level, both in education and intelligence, of the average English private. While in no way doubting his veracity. I should say he enjoys telling a good story. T. Byard.